It has been said that when Claude Monet painted his gardens at Giverny, France, he was creating his art twice. Monet believed that the garden itself was as noble a palette as any primed canvas, and he planned for and planted his gardens with a consistent awareness that what he was creating was, ultimately, beyond even himself. Monet understood that a garden grows and changes over time, yet is an enduring fixture of the land; once created, forever altered.

|

| Spring at Claude Monet's home, Giverny Photo by Ariane Cauderlier Giverny Photo |

Monet worked with color and light in the garden much as he did on canvas with his paintings. He would mix common plants, like daisies and delphinium, with rare species he paid premium prices for. The overall effect of his flower garden, Clos Normand, is a wild, fantastic, overgrown dreamscape.

I am

following Nature without being able to grasp her.

I

perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers.

--Claude Monet

|

| Flower of Life II Wikipaintings |

As much as O'Keeffe appreciated the luscious, and perhaps even lascivious, form of the flower, she also revered the feral starkness of a prairie landscape. She had come to value the varied hues of the sun on the red-brown grass and the promise of rain in the clouds that cooled as they rose above the far off mountains and plateaus.

O'Keeffe spent part of her young adult life as an art teacher in a small, dusty town in the arid Texas panhandle. She spent much of her later life in the stark scenery of New Mexico where she loved exploring the countryside by taking long, rambling walks, a habit she cultivated on the Texas prairie, where she would return home and paint what she felt. O'Keeffe would effectively juxtapose the lush, dewy moisture of a flower in full bloom against the sand brown expansiveness of the undulating grass-land prairie.

|

| Ghost Ranch Landscape SouthwestArt |

Her approach to art as an expression of raw emotion through painting flowers and landscape was new in a world that had only recently accepted Impressionism as an art form that managed to blur the lines of the corporeal concreteness seen in a still life with the painstaking and stoic realism of the Dutch Masters.

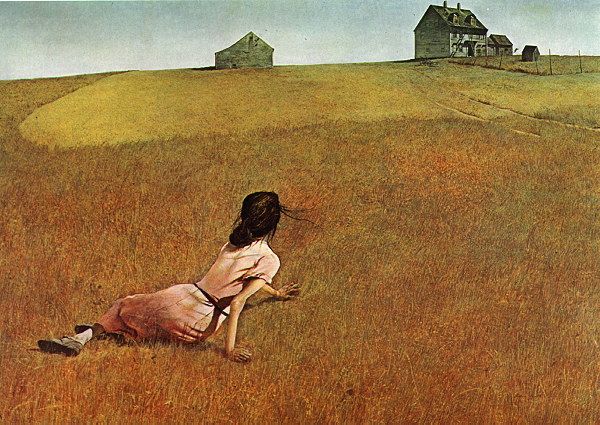

While O'Keeffe quintessentially captured the harsh, brash beauty of the prairie, landscape as raw emotion is epitomized in Andrew Wyeth's renowned depiction of Christina's World. Here Wyeth captures the limited vision of Anna Christina Olson, a neighbor's daughter, stricken by what is often presumed to be polio. Christina, unable to walk upon her own legs and lacking modern aids to mobility, used her arms to drag her lower body about her family farmhouse and acres of prairie. The painting captured the collective imagination of an American public at about the same time that O'Keeffe was introducing the marriage of floral portraits to prairie landscapes entwined with bleached antlers, stark bats with wing unfurled and other symbolic reminders of our own mortality.

|

| Christina's World Andrew Wyeth |

I have come to appreciate these artists who feel an emotional connection to the immense beauty that Nature provides. I love Georgia O'Keefe's open emotional response to being moved by the raw sensuality contained within a single blossom as well as Monet's desire to provide a fragrant feast of a display through his careful cultivation of an array of blooms and blossoms. I value Wyeth's gift of capturing the wind in the grass as it swirls around the fair hair of a child as well as his his unabashed depiction of the limits of life. I, too, have grown to love the beauty of a blossom that dares to bloom on the prairie, in all its moods and windy wildness. My humble attempts to tame it or to coax something from it are often withered by the wind and the intense sun that marches relentlessly across the vast, uninterrupted sky.

Yet, here, on the tawny, sun-drenched, wind-swept prairie, is where passion often lies, flowing in waves like the wind on the grass, waiting for its chance to bloom.